Note: Although this is an older book, Stiff is still interesting, gross, and relevant today. I recently finished reading it and hope you find my review helpful!

Deathly Decisions

Today, legal consent and regulation oversee the use of a deceased body for research or organ donation, but a few centuries ago scientists took an unscrupulous approach to grabbing corpses for their professional use. In need of cadavers for medical school anatomy classes, British medical schools in the 1800s hired resurrectionists to dig up fresh dead bodies from the cemetery. In the darkness of night, a grave digger pried open the top of a coffin, pulled out the corpse by the neck or arms, and covered up the disturbed ground so that no one suspected theft. Resurrectionists were paid handsomely for their work, and medical students practiced surgical techniques on stolen bodies.

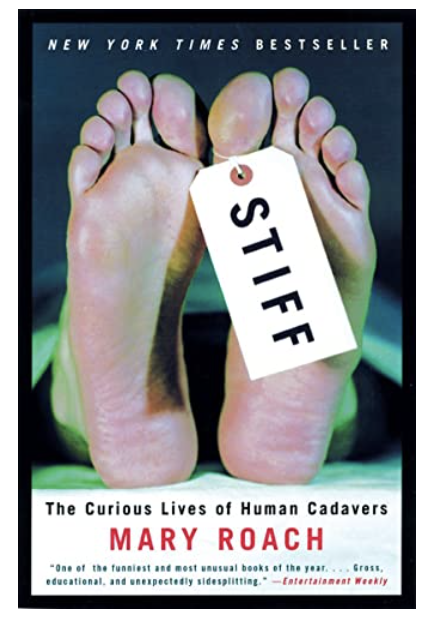

Graphic stories of body snatchers, plane crash autopsies, and postmortem preservation fill Mary Roach’s nonfiction book, Stiff, which was published in 2003 and updated in 2021. Roach is a journalist and author of nature and biology books, and Stiff is her scientific homage to almost everything you didn’t know (or didn’t want to know) that happens to a body after death. From a cadaver head clinic—where surgeons perfect plastic surgery on decapitated heads, to plastination—a method of tissue preservation that involves polymer, Roach educates and entertains with vigor. But don’t be fooled. The aim of Stiff is to convince the reader to bequeath their body to science (or at least be an organ donor).

However, Roach’s desire to normalize whole-body donation is overshadowed by the awe and revulsion her stories evoke. She visits a lab in Michigan where cadavers are used to study the impact of violent car crashes so engineers can build safer cars. She witnesses a male cadaver duct-taped into a driving position and shot with a high-speed piston. Other experiments involve crashing cadavers into concrete walls, which mimic highway accidents. It makes perfect sense that cadavers are used to study trauma on a simulated collision course, but it’s equally disturbing to imagine a deceased loved one getting their head purposely slammed into a glass window at one hundred miles per hour.

At a center in Tennessee that studies human decay for forensic science, Roach demonstrates her willingness to report on locations most people would avoid. Here, researchers learn how to determine the cause of death at a crime scene by observing how the natural environment interacts with a corpse over time. Bodies, in various stages of decomposition, lay outside in a large field fully clothed; they are waiting for wind, rain, humidity, and insects to disintegrate the flesh. Roach’s observations are so descriptive and nauseating that you can practically smell human decay and hear skin eaten away by microbes, but her point is that these cadavers are doing a service for society.

Roach wants you to squirm at these research methods and then agree to have those exact things done to you after you’re dead. She says that a deceased body should be used to advance science or harvest organs because they have no use for their body anymore. She argues that a traditional funeral or cremation is just as gruesome as having your body dissected by medical students, and I admit it’s hard to find a good counterpoint to those claims, but her graphic and grotesque descriptions of cadaver research make it a hard sell.

But Stiff is not all bad. Roach has a gift for explaining anatomy, biology, and the history of cadavers in science, while she spotlights people who work with the dead who put a new spin on the term “rewarding work.” For example, the section where young mortician students prepare a deceased man for his funeral is so eye-opening that it’s worth the cost of the entire book. One student carefully trims away nostril hair because “it gives the decedent some dignity,” while another prepares to sew the jaw shut. They stuff the man’s eyeballs with cotton to retain their shape and put in contact lenses to keep his eyelids closed. Next, they use a basic needle and thread to sew the anus and prevent leakage during the funeral. Finally, embalming fluid, a preservative dyed red, is injected into the veins, giving the cadaver a rosy flush.

The students focus on the positives of their jobs. “If there are parasites, or the person has dirty teeth, or they didn’t wipe their nose before they died, you’re improving the situation, making them more presentable,” rationalizes one apprentice.

Stylistically, Roach interrupts her serious narratives with occasional tongue-in-cheek comedy, sometimes devaluing her professionalism and authority. “If you really wanted to know for sure that the human soul resides in the brain, you could cut off a man’s head and ask it,” Roach says cheekily in a section that questions if the soul resides in the head or the heart. In the chapter on medical cannibalism, Roach jokes that preparing a mom’s placenta in pizza, lasagna, or a cocktail could be brought to the PTA potluck.

Sometimes, I was grateful for Roach’s humor. Still, it made me wonder if she understood the enormity of death, the pain it left surviving family, and the emotional turmoil of body donation. Is it reasonable to expect a person to bequeath a body for research when they just read about decaying donor corpses rotting under the boiling sun in the name of science? To be fair, Roach briefly acknowledges the difficult choices we make during immense grief but stays away from addressing sentimentality. Instead, she wants you to rationalize with facts, which is hard when most people think spontaneously with their hearts.

Although Roach failed to convince me to donate my remains to science, her book was worth my time because it made me uncomfortable. Stiff challenged how I want my body treated and disposed of after death. Am I selfless enough to give away my cornea, heart, or liver? Should my family decide if I get smashed at a car collision course or decompose slowly with nature in a forensic center? Do I imagine an open casket funeral or a more ecologic-friendly burial? Roach’s narrative rattles consciousness and pokes at indescribable discomfort but motivates everyone to reckon with after-death plans.